Anne W. Brumby: Her Life in Athens, Georgia

by Caitlin Short

In the early-morning hours of February 21, 1964, Anne Wallis Brumby passed away at a local hospital after an extended period of illness. She was 88 years old, having been born to Captain John Wallis Brumby and Arabella Hardeman Brumby on May 5, 1876. An article announcing her funeral services, published in the Athens Banner-Herald, provided its readers with a summary of her life here in Athens:

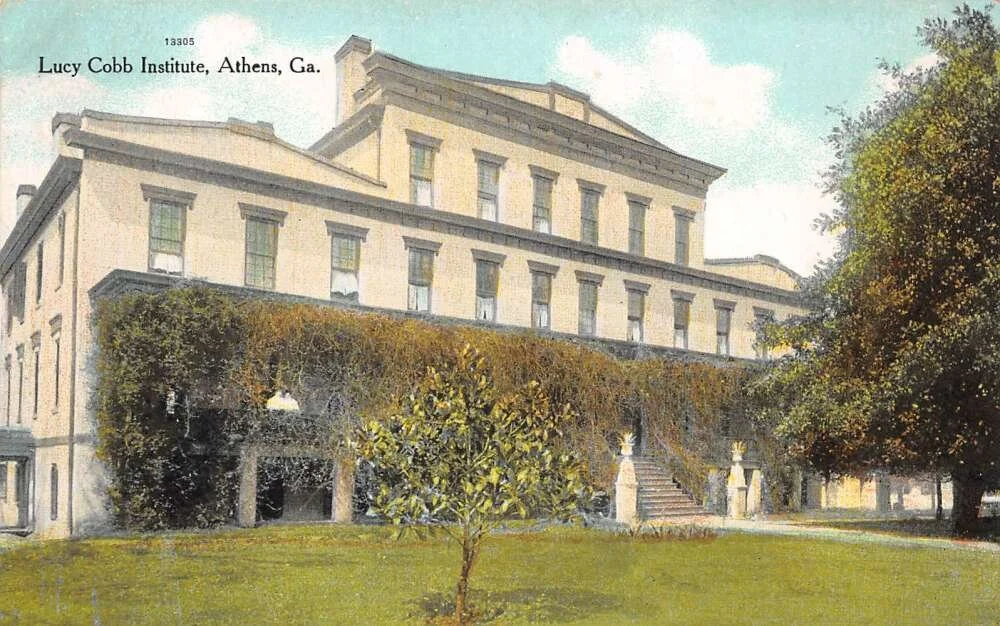

“Miss Anne Wallis Brumby was born in Athens May 5, 1876, the daughter of John Wallis Brumby and Belle Harris (Hardeman) Brumby. As a child, she was educated by her parents. During Miss Brumby’s girlhood days Mrs. Ellen A. Crawford conducted a private school in Athens, a well-known boarding school, and there she received the education that prepared her to enter Lucy Cobb Institute, at that time a finishing school for girls in Athens.

After five years there, she took private lessons from University of Georgia professors before the University was open to women students. When women were admitted, she enrolled as a student and in 1920 received the Bachelor of Arts degree. She attended summer schools at the University of Georgia, University of Tennessee, Columbia and Harvard. In 1925, she received the Master of Arts degree from the University of Georgia.

For nine years, 1908-1917, Miss Brumby was Associate Principal of Lucy Cobb Institute. In 1917, she resigned as Associate Principal and became head of the Department of French at Lucy Cobb, which position she held until 1924. In 1924, Miss Mary Dorothy Lyndon, the first Dean of Women at the University of Georgia having passed away, Miss Brumby became the second Dean of Women in that institution, and while serving in that post, she was also Associate Professor of Education. In 1929, she became Associate Professor of French and gave up her work as Dean of Women. Until her retirement, she devoted her entire time to the teaching of French.

Miss Brumby was a member of Phi Beta Kappa and Phi Kappa Phi honorary societies and also had the advantages of travel in England, Ireland and France. Miss Brumby was a member of pupils and to the University girls in her care much more than a love for and knowledge of the French tongue. Manners, morals, a sense of duty and the desire to do well because it was right were only a few of the virtues she taught both by precept and example. Miss Brumby was an accomplished and dedicated teacher, a fair, just and wise administrator, and above all a lady, in the finest sense of the word.”

This article ends by stating the location of the historic Brumby home, at 343 East Hancock Avenue. It was in this location that the house stood for almost 150 years, and underwent many alterations, before being removed to its current location, at which time it was taken back to its early nineteenth century appearance. Expand the sections of the menu below to learn about Anne’s girlhood years, early education, and her collegiate, professional, civic and social life in Athens as it was presented to the public in historic newspapers.

-

In 1805, Anne’s great-grandfather, Steven W. Harris, was among the first graduates of the University of Georgia. He had come to Athens from Eatonton, Georgia, and he returned to Eatonton post-graduation, where he would practice law, serve as a Judge of the Superior Court, and marry Miss Sarah Watkins. In 1820, Mr. Harris became a member of the Board of Trustees at the University of Georgia, a position which he held until his death in 1828. Sometime after his death, Mrs. Harris and their children moved to Athens, purchasing the home of Dr. Moses Waddel, fifth President of the University of Georgia. Dr. Waddel had purchased this home from Dr. Alonzo Church in 1822, who had the house built with the intention of residing there upon moving from Eatonton in 1819, when he was called upon to fill a mathematics professorship at the University of Georgia.

Mr. and Mrs. Harris had seven children: Sampson, Mary, James, Jane, Stephen, Susan and Arabella. In 1842, Arabella Harris married Benjamin F. Hardeman, with whom she would have two children in Lexington, Georgia: a son named Sampson, and a daughter named after herself– Arabella. On June 9, 1845, when Arabella was only two months old, her mother passed away at the young age of 29 after a “lingering and painful illness,” as stated in the Southern Banner on June 12 of the same year. It was at this time when Arabella became a citizen of Athens, living at the home of her grandmother, Mrs. Sarah Harris, with her father and brother– a home in which she would later raise four children with her husband, Captain John W. Brumby: Mary, Frank, Anne and Wallis.

-

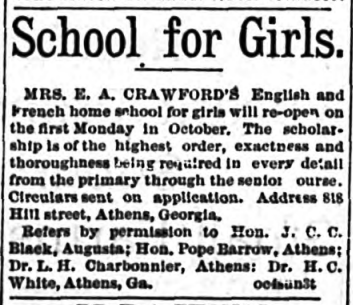

In 1890, when Anne was around fourteen years old, Mrs. Ellen A. Crawford opened a private school for girls in Athens at 818 Hill Street– a school at which Anne was enrolled, after many years of homeschooling by her parents, to begin preparing her for higher education. Several years after its opening, the Athens Daily Banner described Mrs. Crawford’s school as “one of the most thorough and prosperous schools in Athens” and “one of the best of its kind to be found anywhere.” The school took in students from four years of age and up, with the higher classes given opportunities to study the Classics, Mathematics, History and Literature, Music and Art, French and English. For the music courses, Mrs. Crawford used a Mathushek piano from Hale & Conaway. Following her time at Mrs. Crawford’s school, Anne enrolled at the Lucy Cobb Institute. In 1896, an Athens-based chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy was organized by a co-principal of the Lucy Cobb Institute, Mildred Rutherford. At this time, Anne became one of the officers of the chapter’s first executive board.

-

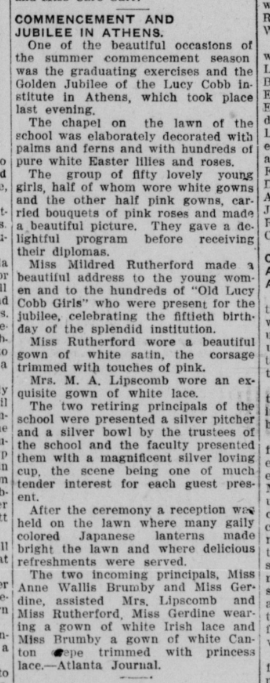

By 1908, Anne was preparing to assume the position of co-principal at the Lucy Cobb Institute, alongside Susan Gerdine. This news was shared by the Atlanta Journal in tandem with an announcement of the Commencement and Golden Jubilee, celebrating the institution’s fiftieth birthday and the class that would graduate that same year– an event at which Anne was in attendance. It took place at the Seney-Stovall Chapel, which was elaborately decorated with palms, ferns, and hundreds of white roses and Easter lilies. Half of the ladies of the graduating class wore white gowns, while the other half wore pink, and they carried bouquets of pink roses. Outgoing co-principal Mildred Rutherford gave a celebratory address, alongside her fellow co-principal Mary Lipscomb, both of whom received gifts of a silver pitcher and a silver bowl by the school trustees in acknowledgement of their retirement, along with a silver loving cup presented by the school faculty.

Following the ceremony, a reception was held on the lawn, which was illuminated by brightly colored Japanese lanterns. According to the Atlanta Journal, outgoing principals Mildred Rutherford and Mary Lipscomb wore a gown of white satin accessorized with a corsage trimmed in pink, and an exquisite gown of white lace, respectively. During the event, they were assisted by incoming principals Anne Brumby and Susan Gerdine, who wore a gown of white Canton crepe trimmed with princess lace, and a gown of white Irish lace, respectively. Anne held the position of co-principal at the Lucy Cobb Institute through her studies at the University of Georgia. She graduated with a Bachelor of Arts in Social Sciences in 1920, putting her among some of the earliest female graduates in the University’s history.

-

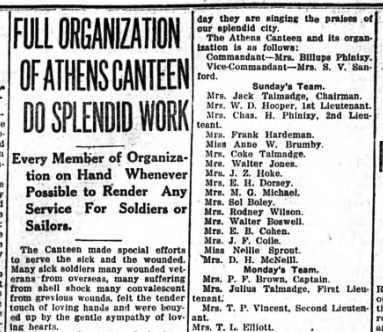

In the midst of her career and her undergraduate studies, Anne was also involved with the Athens Canteen– a civic organization affiliated with the Red Cross. In 1919, Anne was among many Canteen volunteers– primarily women– who ensured that homebound soldiers and sailors traveling through Athens, in varying conditions of mind and body, received a warm welcome and generous treatment. The ladies of the Canteen set up at the Seaboard depot, where they would greet the men as they deboarded trains and offer them food, drink and conversation– and, occasionally, transportation, as was the case of one young soldier who was driven from the Seaboard depot to the Georgian Hotel by the chairperson of the canteen service, Nellie Stovall Phinizy. According to the conductors of these trains traveling across the country, the ladies of the Athens Canteen established a national reputation.

-

After obtaining her undergraduate degree from the University of Georgia, Anne remained among the faculty at the Lucy Cobb Institute as the head of the French department, as well as a member of the alumni association’s executive board. She returned to the University for her graduate studies, and was elected as the associate professor of education and dean of women in 1924, succeeding Mary Lyndon, who died several weeks prior.

Anne was regarded as not only a thoroughly capable educator, but a woman of wonderful resourcefulness and executive ability who would exercise a healthy and inspiring influence over the young women students. At the time of her election, Anne was working toward a Master of Arts degree, which she was awarded in June 1925. During her time as dean of women, Anne was involved with the local branch of the American Association of University Women– also referred to as the University Women's Club– at one time serving as their president.

-

Dan Magill, a columnist for the Athens Banner-Herald, published a column on May 8, 1928, offering his opinion “from the soap box” on the lack of small and conveniently located public parks in Athens. In this column, he highlighted the efforts of the local branch of the American Association of University Women to establish Athens’ first public library– a small but mighty endeavor that served as an example of successful advocacy for public resources:

“For instance, we waited around for years in need of a public library. Every now and then, somebody would start a movement for a library. A meeting would be held and speeches made in which the low price of cotton was attributed to lack of a library. When the time came to discuss funds for building a library everybody wanted to float a big bond issue. That would bring on a little reflecting as to the probable reaction to the tax rate and then everybody would quietly dismiss the idea of a library.

Then, along came the Athens branch of the American Association of University Women. They suggested to a few friends the plan to establish a library here, beginning in a small way and growing up– with the town, so to speak. Well, they succeeded in interesting some people. The money, only a few dollars, was provided. The library was started. It isn’t more than a year old today, but it is well underway, and will be the nucleus of Athens’ big public library some day, if Athens ever has a public library.”

Another article in the Athens Banner-Herald stated that the library committee aimed to buy as many books as possible with available funds, and to be able to grow the library collection over time by renting out those books for a small daily fee. Other organizations and individuals were approached, with people being encouraged to become charter members of the library with a modest contribution of one dollar. The library committee stated in a notice to the public, “As soon as the library assumes sufficient proportions, the association will present it to the city of Athens.”

The University Women’s Club was committed to the betterment of the community, and the proposal of this public library was a point of discussion during one of the Club’s last meetings under Anne’s presidency. Hosted at her home on Hancock Avenue, this meeting also included the discussion of objectives such as educating high school girls on the advantages of a college education; starting a scholarship loan fund for girls to pursue a college education; establishing study groups along the lines of training for parenthood, courses in psychology dealing with the adolescent girl, and studies of music and literature; and sponsoring the establishment of public playgrounds.

-

Anne’s investment in the people of Athens at large was equal to that which she poured into her role as the dean of women at the University of Georgia. Her progressive, growth oriented thinking and her dedication to the success of the student body earned her immense respect. She taught summer school courses, oversaw the formation of new language courses that would allow students who failed in their first term a second chance, and took a special interest in the young women enrolled at the college. In December 1927, as the ten year anniversary of co-education at the University of Georgia approached, Anne took to the college radio station to speak about the high scholastic averages of the female students. She felt that the number of women enrolled at that time– 362 undergrads, and 23 graduates– showed that women want to take full advantage of co-education. Additionally, she made a point to state that the three highest averages in the 1926 senior class were made by women.

-

In 1929, Ellen Rhodes became the University of Georgia’s third dean of women. Anne remained at the college as a member of the faculty in the Department of Romance Languages, where she once again taught French. In March of the following year, she and her sister, Mary, and their friend Mary Strahan, made plans to sail to Paris and spend their summer abroad– a journey on which they would embark on June 7, 1930. About a month prior to departing for Paris, Anne was the honored guest of a dinner hosted at the University of Georgia’s Sophomore house– the residents of which had proposed the house be named for Anne a few years earlier. Not long after her return to Georgia, Anne once again took to the college radio station, this time to speak on “Tours and the Loire Valley in France.”

-

Anne had a vibrant social life, and could often be found on the guest list for dances and dinner parties– on many occasions, as a guest of honor. Her hospitable nature made her no stranger to the receiving lines at various events hosted by the University of Georgia and the civic organizations, honors societies, alumni societies and social clubs with which she was involved, one of these being the Ladies Garden Club. In 1937, for the Club’s first Georgia Garden Pilgrimage, Anne welcomed guests into her home on Hancock Avenue. The home was advertised as one of “Athens’ most interesting homes,” and the article emphasized what an unusual privilege it would be to see the participating homes in their original settings. As a gardener, Anne grew award-winning tricolor camellias.

-

Along with her frequent civic and social activities, Anne remained dedicated to her position in the Department of Romance Languages at the University of Georgia through the years. On October 15, 1948, an article published in the college newspaper, The Red & Black, detailed a set of scholarship awards that were to be named for her and her successor as dean of women, Ellen Rhodes (McWhorter). From there forward, these scholarship awards were to be presented each spring quarter to the two women’s dormitories with the highest scholastic averages– one on the college’s main campus, and one on the coordinate campus. The first dormitory to receive the Anne Brumby Scholarship Award was Mary Lyndon Hall, whose house president accepted the award following a midnight procession through campus on May 11, 1949.

-

By 1961, Anne’s health began to decline. At this time, she and her sister, Mary, were still residing together at their family home on Hancock Avenue. Three years later, a personals column in the Athens Banner-Herald, published on February 17, 1964, stated that friends of Anne and Mary would be “interested to know that they are patients of Monroe Nursing Home in Monroe, Georgia.” Anne died only four days later, having cemented for herself a dynamic legacy that would inspire women for generations to come, and a graveside service was held at noon on February 22, at Oconee Hill Cemetery. Four years following her death, Anne was memorialized with the naming of a new University of Georgia dormitory in her honor.

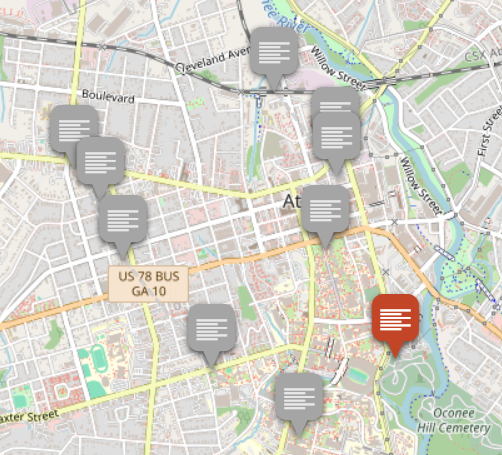

Explore Anne’s Athens

Check out this interactive map to take a self-guided tour of sites around Athens that played significant roles in Anne’s story. Please be mindful that many of the buildings are under private ownership.

We suggest ending at Oconee Hill Cemetery, where you can visit Anne’s grave in the Brumby family plot on the East Hill.

Curator’s Statement

Established in 1973, the Historic Athens Welcome Center is proud to call the c.1820 Church-Waddel-Brumby House Museum our "home." The house was saved from demolition in 1967 by a local group of preservationists during a period of urban renewal in Athens, and was removed to its current site in 1969 for restoration. Since its inception, the museum focused primarily on the first ten years of the house's history, when Dr. Moses Waddel, fifth president of the University of Georgia (1819-1829) resided in the house with his family (1822-1830). However, its history as a private residence spans almost 150 years, with the Harrises, Hardemans and Brumbys having spent the most time here.

In recent years, we have worked diligently to expand our storytelling at the museum. This began with research conducted by Historic Athens intern Sydney Phillips during the COVID-19 pandemic, regarding Black history at the museum as it is connected to the white owners of the house. Following this, I spent around a year in total transcribing the personal journals of Dr. Moses Waddel as digital reference material, during which time I discovered 40 names belonging to enslaved persons. These particular journals were written between 1821-1831. Using context clues within the journal entries, I authored a narrative entitled Enslaved Persons in the World of Dr. Moses Waddel: 1821-1831 , which can be found on our website along with A History of Black Athenians at the House , one of the products of Sydney's work.

Anne Brumby: Her Life in Athens, Georgia is a hybrid exhibit- part digital, part physical- that allows us to continue expanding our storytelling and reimagining how we can make use of the historic space that we are so privileged to be the stewards of, in a way that is respectful of the existing decorative finishes and furnishings. Prior to building this StoryMap, I spent a month and a half or so conducting research, primarily utilizing one of my favorite resources (historic newspapers) to learn about Anne's girlhood years, early education, and her collegiate, professional, civic and social life as it was presented to the public. The physical component of this exhibit was inspired by the descriptions of the clothing worn by the ladies of Lucy Cobb during the Commencement and Golden Jubilee celebration in 1908. On view at the museum from July 7 through September 30, the exhibit showcases a small selection of women's garments that date between 1909 and the mid-1920s, including a 1909 wedding ensemble donated to our collection in 2024.

This will be one in a series of exhibits that rotate at the museum annually. It follows A House of Influence: The Civic Legacy of the Church-Waddel-Brumby House, an exhibit developed for Civic Season by Historic Athens Welcome Center museum collection assistant Jacob Richardson. Following Anne W. Brumby: Her Life in Athens, Georgia, the museum's first floor will be staged for our annual Death & Mourning tours through October.

Urban Renewal and Brumby Hall

As urban renewal altered our historic landscape following WWII, there were more instances of loss than there were preservation successes. Over 300 buildings around Athens were demolished in the name of progress. One of the most unfortunate urban renewal stories in Athens involves Linnentown, a Black community razed for the development of a new dormitory complex at the University of Georgia. This complex includes the dormitory that would be named for our Anne, Brumby Hall.

On various websites, you can learn more about the Athens Justice & Memory Project and how the Linnentown community's former residents, their descendants and their allies have worked to raise awareness of their story and advocate for reparations, as well as a community mapping project conducted in 2022 and the upcoming Center for Racial Justice and Black Futures .